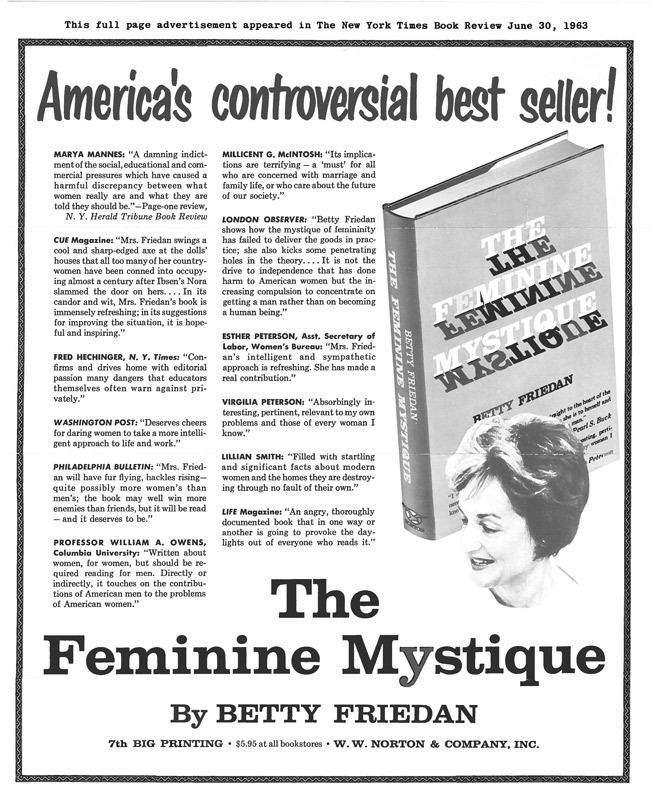

Post your comments below for Betty Friedan's

Feminine Mystique and Sylvia Plath's

Bell Jar. The latter text seems to trap its motifs under glass, so that they swirl around inside with suffocating intensity. Try to catch some salient images by extracting a particular passage for us to close-read in Tuesday's class. I also strongly urge you to consider the points of contact between

The Bell Jar and "Elizabeth Arden," especially with respect to the narrator's direct call out to a displaced reader. Could Esther Greenwood be that "you" whom she summons? Ethel Rosenberg perhaps?

Post your comments below for Betty Friedan's Feminine Mystique and Sylvia Plath's Bell Jar. The latter text seems to trap its motifs under glass, so that they swirl around inside with suffocating intensity. Try to catch some salient images by extracting a particular passage for us to close-read in Tuesday's class. I also strongly urge you to consider the points of contact between The Bell Jar and "Elizabeth Arden," especially with respect to the narrator's direct call out to a displaced reader. Could Esther Greenwood be that "you" whom she summons? Ethel Rosenberg perhaps?

Post your comments below for Betty Friedan's Feminine Mystique and Sylvia Plath's Bell Jar. The latter text seems to trap its motifs under glass, so that they swirl around inside with suffocating intensity. Try to catch some salient images by extracting a particular passage for us to close-read in Tuesday's class. I also strongly urge you to consider the points of contact between The Bell Jar and "Elizabeth Arden," especially with respect to the narrator's direct call out to a displaced reader. Could Esther Greenwood be that "you" whom she summons? Ethel Rosenberg perhaps?

"The Sexual Sell" closely examines an advertising culture that targets women as consumers. When women are kept out of the work force, they obviously have no income of their own, and while they may be the primary players in the marketplace--star shoppers, if you will--their consumer status connects them even more deeply to their husbands who support them. Keeping women's minds subdued, it seems, is only one method of limiting the mobility and power of women in society. Barring them from an education and subsequent income while constantly enhancing their desire to buy serves a practical purpose for the "researchers" in The Sexual Sell. Consider this passage: "Properly manipulated ("if you are not afraid of that word," he said), American housewives can be given the sense of identity, purpose, creativity, the self-realization, even the sexual joy they lack--by the buying of things" (199). Although in her education and aspirations, Esther of The Bell Jar resembles the "Career Woman" far more than the "True Housewife", she interacts with American capitalist culture in a very distinct way. What are your comments on this?

ReplyDeleteI don't recall a direct call out to the displaced reader in The Bell Jar, can anyone point me to it?

ReplyDeleteEsther makes a very clear connection between sex and the family in the scene where she watches a child being born with Buddy. It’s this connection that leads her to ask Buddy about his sexual encounters, and consequently reveals his hypocrisy regarding sex. On pg. 62, she says, “I found out on the day we saw the baby born.” (What she found out was Buddy’s hypocrisy). She never explicitly states why the birth was what lead to this realization, so what do you think Esther is trying to say? How does she say it using the passages on pg. 66 and pg. 67? How does this message relate to the passages from The Feminine Mystique?

Hi, Kenzie! The direct call out to the reader belongs to Zernova's narrator. I was urging us to ask whether or not we could imagine Esther Greenwood (or Ethel Rosenberg) as somehow unwittingly responding to her call. Though no such apostrophe appears in the The Bell Jar, the fantasy of intimacy between US and USSR/Russian/socialist women takes other forms, perhaps, in Plath's book (e.g. with the UN interpreter whom we all might not have met yet).

DeleteAnd thanks for pointing us to this passage. I wonder if we could read it with the alienated-anatomical scene from "Pkhentz," and to what end?

DeleteMackenzie, if I'm not mistaken I think that Anastasia was pointing out the direct call to the reader in Elizabeth Arden, not in the Bell Jar. I could be wrong though!

ReplyDeleteOne thing I thought was interesting about these pieces was the way that Esther rebelled at the "housewifeization" (yeah, that just happened), that she was being forced into at her job. I saw this mostly during the dinner party scene where all the other young, potential-filled ladies were eating properly and neatly, which she was doing absolutely anything she could to eat as much caviar as physically possible. Although this scene to me stood out as comic relief, I think a lot is said about the character of Esther and of the times in the moment. What is she saying about the confines of femininity in this moment? How does she break them, and can you think of any other passages from this text that continue to break these walls?

That's exactly what I had in mind, Emma. Meantime, yes on the neologism! And, to bring your point into conversation with Abby's and Kenzie's above, can we read these moments in TBJ as a way of defamiliarizing the technicolor housewifized model of femininity sold to women through postwar advertising by means of Shklovskiian technique (a la Siniavsky's Pkhentz)? In other words, does TBJ make strange the 50s woman who is otherwise enshrouded in a feminine mystique?

DeleteI think that we can see this right from the beginning of The Bell Jar, evidenced in Esther's constant feeling of emptiness, despite all of her material possessions. This theme can be analyzed on a few levels:

Deletemicro: "I was supposed to be the envy of thousands of other college girls just like me all over America who wanted nothing more than to be tripping about in those same size-seven patent leather shoes..."

mezzo: within the context of her job at the fashion magazine,

macro: on the societal level, with New York City as a symbol of the emptiness of materialism.

Specifically, the passage about make-up in The Bell Jar offers a somewhat contrary perspective to Drakulíc's piece on make-up.

The way Esther/Plath slowly drew us towards the birth scene and her revelation regarding Buddy was quite ingenious, in my opinion. She skirts around the details of her relationship with Buddy, mentioning first that everyone thought they were to be married and then that they'd seen a baby born together. Those details, plus the fact that Esther mentions offhand that she'd spent time in a sanatorium and that she'd gained weight once in her life, led me to believe that she'd had sex with Buddy and gotten pregnant. Until she later reveals the true nature of their relationship, I was shocked and, actually, thought Esther's actions made a bit more sense – that was why she was having trouble with her work, unsure of what she should do, and why she escaped from her small town to New York. I related her to Peggy from Madmen in a way, but the two women went in opposite directions. Peggy soared up and started tapping on the glass ceiling while Esther is floundering in indecision.

ReplyDeleteNow that I've written most of my post on something that didn't happen, what are some assumptions that the reader can make about Esther from the way she writes/thinks? What are some tropes she subverts, or others that she submits to?

http://margotmifflin.com/2009/08/madmen-the-bell-jar-and-the-feminine-mystique/

ReplyDeleteThis article might be of interest to you guys since it ties both of our readings for today to another piece of media we've analyzed, Mad Men. The Bell Jar is quoted in the article: "As Esther notes in The Bell Jar, working women of this period are 'secretaries to executives and simply hanging around in New York waiting to get married to some career man or other.' She imagines marriage and motherhood to be 'a dreary and wasted life for a girl with straight A’s.'" Remembering the two episodes we viewed of Mad Men for class, how can we compare this idea of a desperately single secretary to the characters of both Joan and Peggy (and their differing views on marriage) as well as Betty, who seems to be as bored in her marriage and motherhood as Esther predicts one should be? What do these strong parallels (or lack thereof, if you disagree) say about women during this era?

Eden and Grace, great Peggy-Esther comparisons! Indeed, the writers of MM couldn't not have known or had TBJ and TFM in mind--so thanks especially for this article which makes it explicit, Grace! Perhaps you'll say a little something about it in class discussion?

ReplyDeleteFriedan mentions how the "professionalization" of housework makes women feel that they possess special knowledge and are not just "a general 'cleaner-upper' and menial servant" (205). This gives men an excuse for their so-called helplessness with domestic chores (I can't remember where I read this; it might not have been in the Friedan). Where in The Bell Jar do we see male characters, namely Buddy, benefiting from what they are assumed not to know?

ReplyDeleteThe Bell Jar presents Ester as a woman who is defying the norm of her time. She is clearly incredibly bright and has gone to university instead of staying in the home. "The Sexual Sell" talks about creating a false sense of independence for the housewife. However, Ester seems be on her way to a sense of real independence and a lifestyle very different from what is expected of her. I wonder how Friedman would respond to this. As more of a side note, as I read "The Bell Jar" I found parallels between the women who have more of an "upper hand" in the business world. Maybe this was on purpose?

ReplyDeleteDuring the readings for today, one motif that stood out to me was the idea of class. Esther stands on the edge of high society because, as Emma points out, she rejects the idea of women as housewives, but I also think she stands apart from the other girls because of her class status; from what I gleaned she is one of the few few girls from a "poor" background, and she tries desperately to hide that background. Moving on to Feminine Mystique, the women on whom Friedan focuses strike me as upper-middle-class. These are women with college educations, whose children go to fancy schools, are also expected to go to college and it's seen as outside the norm when they don't.

ReplyDeleteWith that in mind, what role does class seem to play in Friedan's (and Plath's) critiques of society's treatment of women? In what way do their critiques recognize the part class plays in shaping women's role's in society and in what way they ignore class? In what ways do their critiques include and exclude different experiences of sexism systemically and in everyday life?

A quote that stood out in The Bell Jar, said by Mrs. Willard to Buddy that I thought was a good summary of the connection between The Sexual Sell, A Purpose for Modern Woman, and obviously, the novel would be "What a man is is an arrow into the future, and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from". In each, there is a character or narrative that is enforcing the supporting role women play in society. Women must "keep [their husband] Western, keep him truly purposeful, to keep him whole" (Purpose for A Modern Woman). Women must feel a sense of duty and thus be guilted in to buying items in order to maintain their family and sense of purpose. Each piece reiterates the subservient role of the woman and Ester obviously challenges it. But is there a way she does not challenge it? Is it possible for women to completely delegate themselves from stole so thoroughly engrained in their history?

ReplyDeleteI'm sure these posts are supposed to be at least somewhat analytical, but my reaction to these texts is really emotional, as between the lines of text I can't help but see all my mothers and grandmothers, and I feel as though I'm gaining a new and terrifying appreciation for who they were as younger women. Reading The Bell Jar, I can't help but think of my mother, who is, granted, probably seven or eight years younger than Esther, but is close enough in age that I can make the connection. The east-coast collegiate education approached from an outsider's perspective, the young woman trying to make her way as a career woman (not to use Friedan's terminology) in a society that was still so resistant to it. My mother never learned to type so she wouldn't ever have to be a secretary. While I can't see Esther making the same sort of defiance, I also don't think it would be beyond her.

ReplyDeleteI think the Friedan and the Stevenson are crucial to understanding (or, in some cases reminding one of one's preexisting understanding) of the climate in which Esther is coming into her womanhood. And because of the ways in which I identify with Esther's character in the way she reacts to and feels about things, these texts only further enrage me. (Seriously, I had to put the Stevenson down a couple of times to go punch things and scream a little.) I have to say, though, I thought the way the Stevenson tied the cold-war-era "individualism" vs. "totalitarianism" thing into Women's lib was really interesting and I'd like to talk more about it in class because it was cool.

Reading “The Bell Jar” brought to mind Sinyavsky’s “Phkentz” in that it deconstructs the familiar surroundings, specifically in the scene where Esther first sees Buddy unclothed. She gives a rather unflattering description, much like when the alien sees Veronica unclothed . I interpreted this as Esther having an enormous amount of potential power (scholar-wise, work-wise), but unable use that power outside of the social constraints of womanhood in that era. As a result she is alienated by a society that refuses to accept her full self. Where do we still see these social constructs that prevent people--especially women--from embracing both their power and femininity?

ReplyDeleteIf a Phkentz-like alienation is at play here, I should ask the question which arose during our discussion of that piece: do we as readers feel alienated, or does Plath alienate herself as the author? Or is it that it's neither us, nor Plath, but solely Esther? In what other ways can she be considered an alien, or an "other"?

DeleteWe know at least in that she is very alien to the City...

From the analytic to the associative to the affective or emotional, these posts are excellent. Thanks, folks!

ReplyDeleteWe hear a lot about Esther's mother in The Bell Jar despite her never actually being physically present in the text. Esther discusses her mother's opinions on subjects ranging from academics to marriage and sex. These opinions seem to pressure Esther into feeling like she should be "pure" in many ways, which is a developing theme in the novel -- although she says she has decided not to "save herself" until marriage. Do you think Esther's mother's outdated ideas about premarital sex and marriage itself allow Esther to see through the unrealistic expectations of unmarried women during this era, or do they add an unwanted pressure to satisfy societal presumptions? Furthermore, what can we say about the contrast between Esther's reluctance to marry and Sylvia Plath's marriage later in life?

ReplyDelete