Cold-and-hotties, get your closing questions and comments on

The Bell Jar up here by Tuesday at noon, or attach them to the previous post. You should also check out

Adlai Stevenson's commencement address to Sylvia Plath's graduating class at Smith College in 1955. Finally, take a look-see at an actual

goggle-eyed headline from Plath's Smith days.

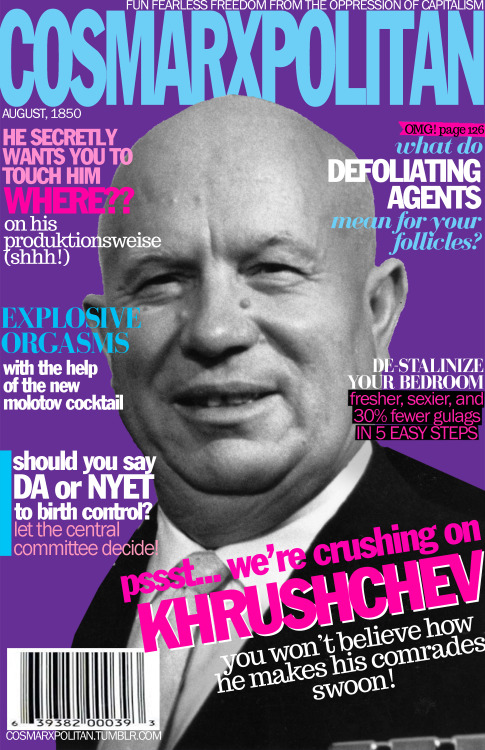

And since this next meeting is our last before the modest October break, here are a couple of relevant blogs to keep your interest piqued about our pet themes of gender, sexuality, and cold war.

Bolshevik Mean Girls

Bolshevik Mean Girls by blogger "It's Raining Mensheviks"and the classic

Cosmarxpolitan . Enjoy!

Knowing that all of this actually happened (or at least came close to actually happening) is pretty freaky and unnerving, especially considering that Plath was eventually successful in suicide. That is, the last paragraph of the novel was supposed to vague and inconclusive, but I suppose we know how it really ends. Because of the close relationship between reality and fiction I'm having hard time treating "The Bell Jar" as an autobiographical novel and not a fictionalized memoir. It seems odd to me to look for themes in purity and purging; in babies, motherhood, sex and birth control; or in the bell jar, depression and the patriarchy, and, end the end, how all of these things relate. I mean, I can draw out themes and analyze symbols, but it feels more perverse because of the story's realness. It feels like that scene when Esther and Buddy are looking at the fetuses in the bell jars except I'm Esther (in the book) and Plath/Esther is a fetus.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I found the relationship between Joan and Esther to be interesting. In many ways they are opposites, yet in many ways they are the same. I'm curious to explore what Joan's character can help us understand about Esther and the bell jar that encapsulates both of them and every other woman in society, and in turn, what Esther can help us understand about Joan as well as the other women (and men) she interacts with throughout the novel.

As we talked about in class, being a women was heavily medicalized throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. I think that the end of the novel in particular highlights this with the presence of doctors, Buddy's visit, and Esther's experimentation with sex and birth control. Almost nothing she does in the end of the book occurs without being overseen by a doctor. As Buddy implies, her experience in the mental hospital ruins her in some way, but what effect did his time in the sanatorium have on him? Hannah points out the themes of purity and purging-to what extent are these topics dealt with through medicine in the book and in life?

ReplyDeleteThe two women who are Esther's primary peers, Doreen and Joan, are both described in opposition to Esther at some point in their existence. However, Doreen and Joan are far from similar characters (though they both subvert social norms in some way, Doreen by going out and partying and Joan by being lesbian [I think]). What can we tell about Esther at the beginning and end of the novel from who she identifies as her opposite? How accurate is Esther in assessing herself? That is, how sure are we that she has an accurate self-image?

ReplyDeleteSince the doctors and nurses are positioned as antagonists in the Bell Jar, I am wondering to what extent the readers are meant to support Esther in her many suicide attempts. Should we feel relieved that Esther has been unsuccessful, or do we share in her disappointment? Do we want her to get "better," or do we see the search for improvement as futile because the source of Esther's frustration is institutional rather than personal?

ReplyDeleteThis is a very interesting point, especially the last question you ask. Esther's problems don't come from her- they originate first from dissatisfying social dynamics in which Esther feels trapped, and then from the doctors. As Abby mentioned, with the medicalization of women, Esther's madness is a commentary on psychiatry, particularly, it's impact on women.

DeleteI think it's important to note the change in opinion that Esther has about her female vs. male doctors. She is extremely opposed to Doctor Gordon, and thinks that he has an alternative agenda for her treatment. However, once she gets moved to the other hospital, and gets treated by Doctor Nolan, her feelings about her treatment drastically change. What does this say about the effeminate characteristics that make Doctor Nolan a good psychiatrist? I think this dynamic says a lot about the gender difference in professionals at this time as well, which we should spend some time thinking about as well.

ReplyDeleteEsther has a complicated relationship with the conventional expectations of her and other women during this era. She flip flops between two extremes, at one point telling Buddy she will never marry and at another telling Philomena Guinea that she "might well get married and have a pack of children someday." Guinea responds by asking, 'But what about your career?' (page 220). Esther resents the poet for this comment, calling her a "weird old [woman]," but she also dismisses her mother's old-school ideas about marriage, motherhood, and sex. However, when she is in the doctor's office with several mothers, she criticizes herself for her lack of maternal instinct: "How easy having babies seemed to be to the women around me! Why was I so unmaternal and apart? Why couldn't I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby like Dodo Conway?" (page 222). What does this inability for Esther to choose a path say about the pressures of such expectations? Would it be helpful if she were to choose one of these women, or another, such as Doctor Nolan whom she has developed a liking and trust for, as a mentor? How do her relationships with other women in the novel further influence and alter her opinions about marriage and motherhood?

ReplyDeleteThe idea of feminine roles in this book has been interesting to look at, especially considering the time period. As we've discussed, during this time, the "norm" was for the woman to marry a man and live her life as a housewife. However, immediately we see Esther is defying this norm by going to college and educating herself. However, as she disintegrates into psychotic madness, she becomes less and less educated as she cannot write or read anymore. In the midst of this we meed Dr. Nolan, who is a female doctor. Her name in itself is interesting as she is a person with a typical male name in a typically male profession...yet, she is a woman. Not only has she gone to college, but she has worked her way to a doctorate degree. Esther puts trust in Dr. Nolan. However, Dr. Nolan seems to be the only doctor Esther trusts (noting the other doctors in the book are male). What could this imply about women/gender roles and possible double standards held.

ReplyDeleteBirth is portrayed as something dirty or grotesque; take, for example, the birth scene with Mrs. Tomolillo, or the pickled fetuses. On the other hand, rebirth is a cleansing, liberating experience, such as the scene where Esther awakens from her shock therapy treatment with Dr. Nolan and feels the bell jar “suspended”. Could we say, then, that birth and rebirth are two separate entities? Why is rebirth “cleaner” than birth?

ReplyDeleteReading this last section of the Bell Jar, I began to consider Esther's position as a writer struggling to locate and assert her voice outside of the patriarchal economy of language (we might consider this the bell jar). When she returns to her mother's house, Esther becomes obsessed with the idea of writing a novel, yet her handwriting deteriorates, rendering her incapable. On the subject what she terms feminine ecriture, feminist theorist Helene Cixous posits

ReplyDelete"Woman must write herself: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies-for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Woman must put herself into the text-as into the world and into history-by her own movement."

I'm really interested in how we might view Esther's (or Plath's, for that matter) compulsion and struggle to write as an example of feminine ecriture- an experience that is significantly tied to the body. What does Esther write about (or fail to write about) over the course of the novel, and how might we see these instances as representing (or trying to represent) distinctly female experience. Does Esther finally locate a voice by the end of the novel and escape the bell jar? If so how, and how are these concepts tied to her embodied experience?